Trauma-informed practice benefits everyone, regardless of one’s life history. At its core, trauma-informed practice is a way of being in relationship to others that supports safety, choice, and healing. Parenting, teaching, coaching, or mentoring in a trauma-informed way isn’t all or nothing. You don’t have to be perfect to get started – and bringing just one element of trauma-informed practice into your relationship with young people can help diffuse the toxic stress that underlies many of trauma’s negative effects. What’s more, relating to the teens in your life in a trauma-informed way can improve YOUR own well-being, as well as theirs.

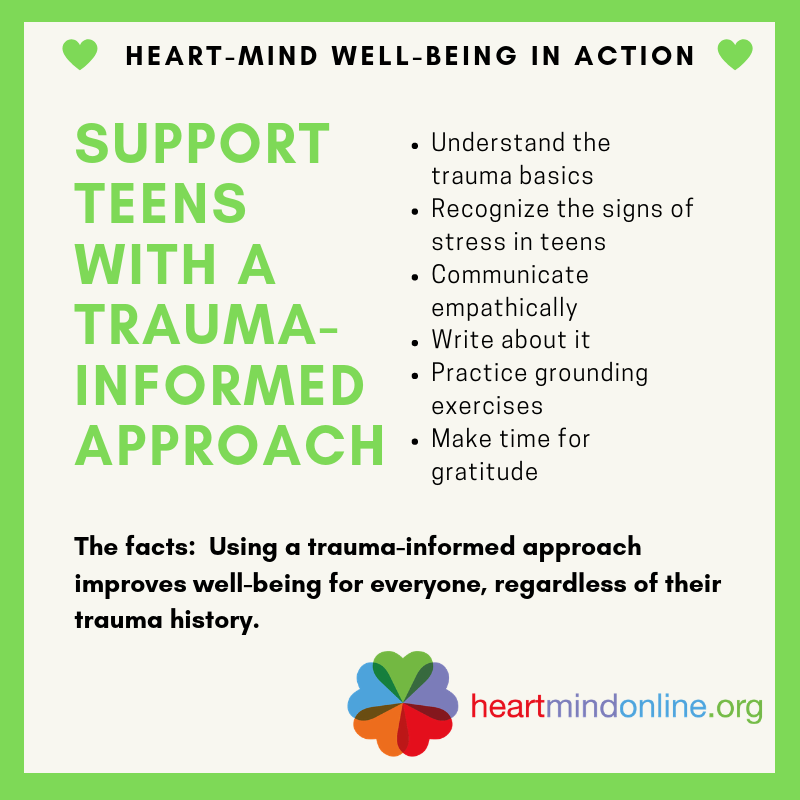

Here are 6 simple ways you can cultivate a trauma-informed approach in your relationships with teens today:

1. Understand the trauma basics

While trauma can take many forms, it typically arises from an unexpected, unwanted experience that a person is unprepared for and cannot prevent or stop.

This kind of experience manifests as trauma when a person’s brain and body are overwhelmed and cannot cope with or integrate the ideas and images that are triggered.

When this response is triggered in a chronic or sustained way, it can result in traumatic toxic stress, and lead to harmful lasting changes in the very structure of the brain.

2. Learn how to identify the signs of stress in adolescents

Although many signs of stress are common at every age – such as changes in eating and sleeping patterns, irritability, emotional reactivity, and withdrawal – teens may also show they are stressed in ways unique to their development. For example, a stressed-out teen may distance himself from parents, family, or long time friends, or react to inquiries of care with aggression or hostility.

While signs of stress may be perceived as “negative” behavior, they are really just a teen’s (often unconscious) way of coping with physical, psychological, and/or emotional overwhelm. If you can understand the struggle behind their behaviour, you can respond with awareness that the adolescent in your life is going through a difficult time, and that they themselves may not understand why they feel – or act – the way they do.

3. Ask the right questions – and respond with empathy

Instead of asking “What is wrong with you?,” ask “What has happened to you?". And then LISTEN. When you feel ready to respond:

1. Use clear, simple language to let them know that what happened was not their fault.

2. Let them know that what happened is not a reflection on them as a person.

3. Show empathy by demonstrating you have heard them and understand how they are feeling, without judgment.

Asking a teen about their experience in this way gives them the chance to share their feelings without feeling like they are the problem. Once they have shared whatever is causing them to feel or act stressed-out, you will be able to team-up to handle the issue together.

For an in-depth guide on trauma-informed communication see this Trauma-Informed Practice Guide.

4. Write it out

Writing about stressful or traumatic experiences improves physical and psychological health and promotes well-being. The deeper and more emotional the experience, the greater the benefits of writing about it - so long as one feels safe to do so and has support to process strong emotions that may arise. Writing can be a one time thing – or become a daily habit. It's as easy as 1 - 2 - 3:

1. To help the adolescent in your life get started, help them find a safe, confidential place to write, such as a personal notebook or computer. They could even write a note on their phone, or an email to themselves.

2. Next, set a time limit, and provide a reminder of the time half way through. No one likes to run out of time to write, especially when dealing with big emotions.

3. Invite them to bring to mind a stressful event or experience, and prompt them to recall their thoughts and emotions about it. You could also ask them to reflect on how the experience has affected different parts of their life – such as family life, relationships with friends, extra-curricular activities, etc.

5. Get grounded

Invite your teen to place their arms across their chest, hands open, with palms resting on the body. If this is a comfortable position for them, invite them to gently alternate tapping one hand then the other against their chest, in a rhythm that feels good to them. Eyes can be open or closed. Once they have found their rhythm, you can also invite them to notice their breathing. Keep going for a couple of minutes.

This technique, called the Butterfly Hug, is just one of many different grounding exercises that can help bring a stressed-out teen back into the present moment through moving and breathing. Bonus: grounding exercises can help you find your center too, so join in if you like!

6. Make time for gratitude

Consider starting a Gratitude Jar in your home or classroom. Invite participants to anonymously write down one thing they are grateful for each day, big or small, on a slip of paper, and put it in the jar. When things feel tough or an adolescent is having a hard time, suggest they pick an item (or several!) from the jar as a reminder of sunnier times. To extend this activity, you could also ask them to add to the gratitude jar when they are feeling down – while this might feel challenging, it can go a long way in brightening mood and opening up perspective.

Looking for even more tools for your trauma-informed tool-box? Check out our video series on Trauma-Informed Yoga for Teens! In this series, trauma-informed yoga therapist Nicole Marcia demonstrates a short seated breathing and movement practice to help teens calm and ground in "Heart-Mind Yoga for Trauma and Stress", and joins Heart-Mind Online in a Q & A session about the importance of building safety, compassion, and choice in relationships regardless of one's trauma history.

See how teachers are putting trauma-informed approaches into action in the classroom in order to better support all their students in this short video.

This definition of trauma-informed practice is adapted from the British Columbia Ministry of Child and Family Development's publication Healing Families, Helping Systems: A Trauma-Informed Practice Guide for Working with Children, Youth and Families (November 2016).

When students are traumatized, it affects their teachers and caregivers too. When the effect is significant, it is called "vicarious trauma" (Jenkins & Baird, 2005).

Even if you haven't experienced vicarious trauma, implementing a trauma-informed approach can help you feel and cope better as you relate to the young people in your life.

See this article and this article to learn more about vicarious trauma in the classroom.

Trauma in early life can result in toxic stress, which leads to lifelong negative health effects such as learning impairments, behavior challenges, and deficits in physical and mental wellbeing (Shonkoff et al., 2012).

In the brain, information that we receive through our senses moves from the “gate keeper” that processes external stimuli (thalamus), to the “smoke detector” that alerts us to threats (amygdala), the “filing cabinet” that makes connections to past events and memories (hippocampus), and finally the “executive” that makes rational judgments and decisions based on the information it receives (prefrontal cortex).

When we experience a real or perceived threat, the “smoke detector” is triggered into an alarm state for our protection – what we commonly refer to as the “fight-flight-freeze response”. This can be felt in the body as increased heart rate, quickened breathing, and muscle tension, and other individualized symptoms. While this response is meant to protect us, the trade-off is that it kicks the “executive” offline, and therefore significantly limits our ability to regulate emotions and think and act rationally.

Negative impacts of traumatic toxic stress and associated brain changes include (Shonkoff et al., 2012):

- experiencing normal every-day experiences as life-threatening events

- development of “maladaptive” coping skills

- suppressed immune system, increased risk of infection, and delayed wound healing

- inflammation

- long-term problems with learning and memory

- impulsivity

This video explains the link between traumatic toxic stress and lifelong health challenges.

According to the American Psychological Association, children and teens may communicate their stress differently from adults, especially nonverbally.

This evidence-informed Trauma-Informed Practice Guide was produced by the BC Provincial Mental Health and Substance Use Planning Council (2012).

A number of studies support the relationship between writing about trauma and improved wellbeing. See the American Psychological Association's publication on this topic for more information.

More trauma-informed grounding exercises can be found in this publication from the Center of Excellence for Women's Health.

The Butterfly Hug is one part of a larger protocol called EMDR, which is used to help children and adults process and heal from trauma.

A 2012 study found that American male and female college students who felt more grateful, fortunate, relieved, and appreciative towards life in the hours and days following a traumatic event experienced fewer and less severe PTSD symptoms.

This conclusion builds on similar findings from a 2009 study, which studied post-trauma gratitude in female college students.